News

Internet Media Turns A Third of a Century Old. 2026 Promises More of the Same: Upheaval

One of the first ad banners in history, AT&T's prophetic "You Will" campaign, from HotWired (of Wired magazine) and other sites, 1994.

2026 marks 33 years since Marc Andreesen invented the web browser, 32 since AT&T’s prophetic “Have you ever clicked your mouse right HERE?” ad banner, and 30 years since DoubleClick pioneered ad-tech, Rex Briggs invented brand lift surveys, and Procter & Gamble, Yahoo and GoTo conjured the scourge of cost-per-click ad pricing.

Like all of us at that time in our lives, “new media” finds itself pondering weighty questions of adulthood like, “What the hell am I doing with my life?” “Why do I keep repeating these same terrible patterns?” and “Would my parents even be proud of me?”

The industry that promised 1-to-1 targeting still thrives on click farms, vaunted accountability really means impenetrable statistical hokum, and all-knowing automation remains directed by gut instincts.

Yet 2026 feels like another of the rare hinge years, akin to the shift to programmatic a decade ago, when the foundational architecture of digital media changes, not just its surface tactics.

It’s worth remembering the trail of industries and companies already reshaped or erased in these waves. Once mighty print media is now the realm of bowtie-wearing nostalgists. The era of the Big Three (martinis and broadcasters) now sits in a nursing home with its mad men protagonists. Portals like Yahoo and AOL, once the center of the web, are brand ghosts. Agencies like Modem Media, Organic, Tribal DDB, and iTraffic defined early digital but no longer exist. Even the engines of the first ad-tech boom—Overture, 24/7 Media, DoubleClick, ValueClick, BlueKai, AppNexus—have been absorbed, dismantled, or forgotten.

And yet the next transformation is already underway. Below are the key advertising trends that will define 2026 and the decade to come, with AI omniscience, identity collapse, supply-chain contraction, and shifting media economics combining to reset the rules once again.

1. Barbell Market of Ad Tech and Publishing

The middle of the market continues to erode. Mid-tier DSPs and SSPs without proprietary data or differentiated supply are losing relevance, as are mid-sized publishers reliant on open-programmatic revenue. Identity decay, shrinking margins, supply-path optimization, and tighter control of demand all push the ecosystem toward a barbell structure. Large platforms and specialized niche providers can survive; the middle struggles to maintain durable economics. The open programmatic ecosystem is contracting, not expanding.

2. Retail Media 2.0 and the New Walled Gardens

Retail media networks have expanded far beyond on-site search placements into full-stack platforms with closed-loop attribution, proprietary identity graphs, and integrations into CTV, DOOH, and off-site display. Their advantage is transaction-level truth, which no other channel can match. As identity degrades elsewhere, RMNs become central sources of targeting, measurement, and audience extension. They will continue to draw budget from open-web display, brand advertising, and promotional programs across the retail ecosystem.

3. Ads as Code: The API-ification of Ad Serving

Ad serving is shifting from a monolithic platform into a modular execution layer controlled through code, as Brian O’Kelley has observed. Creative logic, pacing rules, bidding models, and optimization frameworks are increasingly set via APIs rather than UI controls. Programmatic becomes infrastructure rather than marketplace. This enables federated auctions, server-side decisioning, and bespoke bidding logic outside legacy DSP structures. Intelligence moves from the exchange to the advertiser’s own model.

4. Reinforcement Learning Replaces Rules-Based Optimization

Buying logic is shifting from rules-based bidding to adaptive models that optimize for incrementality, profit, and lifetime value. As user-level signals weaken, platforms must learn from incomplete feedback, turning audience expansion, pacing, and creative selection into reinforcement-learning problems. Products like Performance Max, Advantage+, and Amazon’s automated formats reflect this shift, even as their underlying models remain opaque. Meta aims for fully automated advertising by 2026, with others close behind. Advertisers set objectives and let the systems take over, often with more faith in platform alignment than careful evaluation. The need for independent effectiveness testing grows as automation expands.

5. Identity’s Dirty Secret: Clean Rooms, Dirty Data

Identity is fragmenting faster than the industry can patch it. Clean rooms proliferate but they often match limited, noisy data to similarly incomplete datasets. Deterministic identifiers are scarce, probabilistic signals are inconsistent, and interoperability remains elusive. The tools improve while the underlying inputs degrade. The industry continues to discuss precision while working with persistent imperfection.

6. MFA 2.0: Junk Thrives in a Machine-Buying Marketplace

Made-for-Advertising sites are not a moral failing; they reflect the incentives of the marketplace. They are likely to gain prominence in 2026, not recede. As automated bidding relies on broad, surface-level signals, MFA becomes more attractive to the algorithms buying most open-web media. Cheap, predictable traffic keeps these systems stable while legitimate mid-tier publishers contract. The industry’s talk about transparency and quality remains largely aspirational, and many buyers still default to set-it-and-forget-it approaches. In an automated marketplace, Goodhart’s Law applies: if a metric can be gamed, it will be. MFA prospers because it aligns with how the system rewards performance today.

7. CTV and Retail Media Succeed Because They Are Closer to the Money

CTV’s growth is driven less by shifting consumer behavior than by structural efficiency. It has fewer intermediaries, higher working-media ratios, and a cleaner identity framework than open-web display. Retail media succeeds for an even simpler reason: retailers own the point of sale and the data that governs it. In both cases the advertiser moves into channels where spend is more directly tied to commercial outcomes and less dissipated through opaque supply chains. Budget follows efficiency, control, and proximity to the transaction.

8. Unified Measurement Platforms

Multitouch attribution has waned with the loss of user-level signal, but most marketers are not adopting true randomized experiments at scale. Instead, a new class of measurement platforms has emerged, combining quasi-experimental methods, synthetic controls, incrementality modeling, attribution logic, and modern MMM into cohesive systems. Some operate through always-on pipelines, others in cycles, but all aim to reconcile modeled and experimentally informed outputs into unified reporting. Companies such as Mass Analytics, Arima, Measured, Haus and LiftLab are defining this transition.

9. Cross-Media R/F Measurement and the Aquila Ambition

Aquila, the ANA’s latest effort to unify reach and frequency across linear TV, CTV, YouTube, social, and digital, addresses a real need in a fragmented landscape. But it is attempting to solve a problem of near quantum-level complexity. The industry has long prioritized counting impressions because that is what advertisers buy, while investing considerably less energy in the easier and more meaningful question of causal impact. R/F remains a how-long-is-a-piece-of-string problem, and Aquila inherits the same structural constraints that limited earlier attempts. It reflects a genuine appetite for independent measurement, but its progress depends on cooperation from platforms that benefit from opacity.

10. Bots Advertising to Bots

AI search is becoming a no-click environment, with AI Engine Optimization already displacing SEO in many categories. Consumer decision-making is shifting to AI shopping agents that evaluate products and transact on behalf of users. On the advertiser side, automated bidding systems increasingly manage spend without human involvement. As both sides of the marketplace automate, the early outlines of machine-to-machine advertising emerge. Media-buying bots will negotiate with consumer shopping bots, and more commerce will occur without human intermediaries or the psychological levers that once defined advertising’s role.

Three decades in, digital advertising continues to prove one constant: the ground keeps shifting. But 2026 feels less like another incremental turn and more like a structural reset, one that rewrites the economics, rewires the infrastructure, and moves much of the decision-making from people to systems.

The only thing AI can't do in advertising is measure true ROI

“You’re going the wrong way, dammit!” (The Poseidon Adventure, 1972)

AI is the future advertisers deserve.

Someone recently asked for my take on the WSJ opinion piece AI Is About to Empty Madison Avenue, whether I thought it was overhype or not. In short, no, I don’t think it’s hype.

Industry watcher Don Marti observed in a recent piece that advertisers could defend themselves from losing the advertising game to Big Tech. (They could do it for themselves by using higher-quality measurement techniques. Better yet, the IAB, ANA and other bodies could refer to the blueprint for fixing the whole ROI mess, which Marti cited, that I wrote in AdExchanger more than a year ago.) But in a piece he wrote a couple of weeks earlier, he makes a more convincing argument that they probably won’t, because they’re sleepwalking into oblivion.

I think the AI hype is real. The saying goes that we regularly overestimate the impact of new technologies in the short term and underestimate their impact in the long term. But in this case, the future is already here. AI is moving at the pace of a runaway train.

Not all profound technical advances fundamentally alter professions. Photography, for example. While film manufacturers and processors were rocked, and camera makers lost significant market share to high-quality cell phone cameras, photographers themselves have remained strongly employed. It’s a case of Woody Allen’s Law: 80 percent of success is showing up. Someone still needs to attend the wedding, the bird-watching expedition, the celebrity outing to hold the camera and click.

But that’s not so much the case with most advertising jobs. There’s nothing particularly physical to do. AI is already showing up with the skills needed to do most of the jobs in advertising: understanding the brief, planning the media, developing the creative, executing the buy, delivering and counting the impressions. That whole value chain sits squarely in AI’s sweet spot. And it can crank it all out in minutes, take endless feedback, and make revisions with the most insidious can-do attitude imaginable, without so much as an eye roll.

Tilly Norwood, Sora 2, Advertising Context Protocol: the writing is scribbling on the wall so fast you’d think AI was writing it itself.

This Ad Age story about Butler/Till claiming to have executed the “first” fully AI ad campaign, soup to nuts, is likely to read like a quaint footnote in a year’s time. Talk about a dubious claim to fame. More like an epitaph.

Google, Meta, and Amazon already command the lion’s share of ad spending, and they’re highly automated and increasingly AI-driven. Zuck has said he envisions cutting out all the middlemen and automating all components of the ad stack between the brief and the conversion, which sounded boastful a few months ago but now seems blindingly obvious.

I had an aha moment a couple of weeks ago while attending a Sports Media summit hosted by Operative. Carter Satterfield, a Google Cloud sales executive, shared this story. He’s a big sports lover, spending hours each week coaching his son’s hockey team. On the train ride to the conference, he paused his scrolling to watch a video ad featuring a father and son bonding over the kid’s hockey team. When the kid scores a goal at the end of the ad, Carter realizes he’s wearing the same jersey number Carter himself wore all through high school.

“I can’t be sure it was an AI-generated ad, but it certainly could have been — all of the details are there in my social feed to put it together,” he said. “I don’t normally cry on Amtrak. But I did this morning.”

When’s the last time you could even remember an internet ad you’ve seen? And here was one that brought a seasoned ad professional to tears. It felt like a real tipping point. I’ve contended for years that one-to-one marketing was the biggest fallacy of digital advertising, since the ads weren’t really designed for or targeted to one person. But now, they literally can be.

None of this is to say the future of advertising is going to be better than it was. Or more effective. I’m old enough to know how to spell “bologna” because my baloney has a first name. Advertising impact used to endure for a lifetime.

All that said, there is one thing AI cannot do accurately — the most important thing: measure ROI accurately. But perversely, advertisers just don’t seem to care.

ROI for most advertisers is falling in inverse proportion to Big Tech valuations going up. Advertisers are steadily paying more for less ROI, and Google, Meta, and Amazon are laughing all the way to the blockchain.

If there is one thing marketers have even heard about causation — which, of course, is the ultimate point of advertising, causing consumers to buy your product who wouldn’t have otherwise — it is that correlation is not causation. But AI, you see, is nothing but correlation. Very fast and very sophisticated statistical inference. The fact remains that to truly know what is having an effect, you need to conduct a randomized experiment: subjects assigned at random to a test or control group, presented with an intervention where they are either treated or not with the stimulus of interest (the ad), and measured against the outcome of interest (incremental sales).

A click isn’t that. Attribution modeling isn’t that. Synthetic controls, matched-market tests, double-debiased machine learning, stratified propensity score modeling, and all manner of other “baffle them with bullshit” mechanisms of statistical inference are not that. Those are all forms of correlation. True experiments — randomized controlled trials — are really the only way to know, really know, what kind of effect a marketing strategy is having.

But we don’t need AI to tell us that most marketers will settle for lesser evidence. Self-reporting AI “optimization” engines with Newspeak names like Performance Max and Advantage Plus gobble up ever larger shares of ad spend, while marketers watch their cost-per-acquisition rise.

I used to think about this stuff and feel like Reverend Scott, Gene Hackman’s character in The Poseidon Adventure, screaming at the people convinced they needed to go to the ship’s bow, now underwater, to get out instead of following him to the engine room, now above water, because the ship was upside down.

How does it even make basic business sense that the seller would devise systems that optimize the deal to the buyer’s best interest, not the seller’s own?

“You’re going the wrong way, dammit!”

But over the years, I heard from enough people to realize that whether the advertising works isn’t really the priority in the advertising business. Even though, of course, it should be. What they mean is that it isn’t their priority, in their job function, or in their self-interest. Their priority, and that of their colleagues across the advertiser, the media company, the agency, the whole stack, is simple: spend the money. Spend it as fast as you can, lest, God forbid, there’s budget left over and you get less next time. Whether it really works or not isn’t their concern, so long as they have a nice chart to show their boss afterward. Test and learn be damned.

Shoot first and ask questions later. Kill ’em all, let God sort ’em out.

All I can do is preach. Most people probably think I’m just an old man shouting at clouds. But here and there someone hears me who recognizes the truth in what I’m saying, and I can help a few souls at a time, like Reverend Scott.

What do I think AI portends for advertising? Mothers, don’t let your babies grow up to be cowboys. Or, as Frank Zappa put it: don’t you know you could make more money as a butcher?

Foundational Models for MMM: Interesting, but Built on a Stable Base?

Amazon Ads recently published an intriguing whitepaper proposing a “foundational model” approach to Marketing Mix Modeling (MMM), analogous to how large language models like GPT learn generalizable patterns across many data sources.

It’s an appealing idea: a shared, privacy-safe model that learns from many brands, reducing noise and cost while improving consistency. But I can’t help wondering whether this foundation may rest on shifting ground.

MMMs are, by nature, models. They depend heavily on the assumptions, priors, and data chosen by their modelers. A “foundational” MMM trained on hundreds of brand-level models risks compounding those assumptions rather than correcting them. And when synthetic data enters the mix, the system depends further on abstractions. (See our recent blog post on the risk of AI designing ad optimization on non-experimental assumptions of causality.)

It brings to mind Nassim Taleb's cautions about systems built on interconnected dependencies createing fragility, e.g., financial models leading up to the 2008 mortgage crisis. When many players adopt the same flawed premise, the system becomes brittle.

Aside from one passing reference, what's missing from the whitepaper is a discussion of validation through high-quality experiments. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) remain the best evidence for causal advertising impact. In the hierarchy of evidence, only meta-analyses of many RCTs ranks higher. The industry should focus on building toward benchmarks of incrementality RCTs to calibrate and test any MMM foundation, preventing models from recursively learning from other models.

And it’s worth remembering who is proposing this. Amazon is now in the MMM business, joining Google’s Meridian and Meta’s Robyn. As I argued in The First Principle of Honest Advertising Measurement Is Independence from the Media, credible measurement depends on independence. It’s hard not to be cautious when the companies selling most of the media are also building the tools to “prove” its ROI.

Foundational MMMs could be a leap forward, but only if their footing is grounded in experiments, not self-reference. Don't build sand castles on the beach at low tide.

(Join the discussion of this essay on LinkedIn.)

The First Principle of Honest Advertising Measurement Is Independence from the Media

When you buy a house, you rely on the surveyor and the structural engineer—people who don’t work for the seller. When you pick a restaurant, you trust the health inspector’s “A” in the window, not the chef’s Yelp review. When you invest, you care that the books have been vetted by an independent auditor. Yet in advertising, marketers routinely let the seller grade its own reporting.

That contradiction should make any serious business leader pause. The single most important principle of credible measurement—independence—is still the rare exception in marketing.

The missing audit culture

Across mature professions, independence is non-negotiable. ISO/IEC 17025 requires that testing laboratories “be impartial and be structured and managed so as to safeguard impartiality,” ensuring protection from undue influence or conflicts of interest. The U.S. GAO’s Yellow Book demands that auditors be organizationally independent from those they audit. Clinical trials rely on independent data-monitoring committees to stop studies if conflicts distort findings (ISO; GAO; ICH Guidelines).

The logic is the same everywhere: no matter how advanced the math, if the measurer benefits from a positive result, the credibility is shot. Advertising somehow missed that memo.

A cultural blind spot

Many advertisers genuinely want to measure impact better, but legacy incentives often get in the way. Marketing departments are rewarded for deploying budget efficiently, not for proving whether that budget truly drove incremental sales. It’s understandable, but it creates a blind spot.

Meanwhile, there’s no shortage of metrics: reach, impressions, viewability, clicks, attention, engagement. Each enjoyed its moment in the sun, but none answers the CFO’s central question: How many sales happened that wouldn’t have happened without the marketing spend?

Too often, advertisers accept ROI reports produced by the same entities selling them media or managing their buys. Agencies and platforms rarely hide their preference for internally run “studies” that tend to deliver friendly numbers. Vendors openly admit (over drinks with other vendors) that clients rarely prize accuracy in reporting results. One senior product head at a major agency told me, “Why would we want third-party randomized controlled trials? That only introduces risk for us.” A top consulting firm, hired by a major digital platform, confided that they use that platform’s internal synthetic-control mechanism “because the results are regularly favorable for them.”

Like drunks using lamp-posts: for support rather than illumination, What independence protects

Independence is not a nicety; it’s the foundation of credible causal inference. It protects against three forms of bias:

In design. When the party that profits from the outcome designs the test, parameters conveniently align with its interests.

In analysis. Data processing, covariate selection, and modeling choices can subtly tilt results. Independence enforces transparency.

In interpretation. Even an honest analyst may face pressure to present “directionally positive” findings. Structural separation shields objectivity.

In statistical terms, independence reduces systematic error, the enemy of validity. In business terms, it’s an insurance policy against self-deception.

Other fields learned this long ago

Financial markets insist on auditor independence because self-auditing destroyed companies from Enron to Wirecard. Laboratories maintain impartiality accreditation (ISO 17025) because test results affect safety and trade. Clinical researchers separate trial oversight from sponsors to protect patients and truth. Forensic labs maintain chain-of-custody independence to keep prosecutors from tainting evidence (ISO; GAO; ICH; National Academies Press).

Advertising commands billions in corporate capital every year. Why should its measurement standards be lower than food safety or bridge engineering? Granted, no one dies when campaigns underperform, but companies live and die by market share, a zero-sum game where those who measure best have a valuable edge.

A few bright spots

There are encouraging examples, such as Netflix, eBay, and Indeed, which have built experimentation cultures rooted in transparency and rigorous testing. They prove that independence and scientific discipline aren’t academic ideals, they’re competitive advantages.

More advertisers are beginning to follow suit. For those genuinely striving to optimize media spend, demanding verifiable incremental impact isn’t risky, it’s liberating. It clarifies what truly works and earns credibility across the business.

What independence doesn’t mean

It doesn’t mean outsourcing everything to a third-party vendor. Advertisers themselves are independent from the sellers and can build capability in-house. The key is structural separation: the people whose performance depends on campaign success shouldn’t be the same people validating its impact. The CFO’s team doesn’t audit its own books; marketing shouldn’t either.

Yes, I run a company that performs independent experiments for advertisers. I have skin in the game. But the principle stands regardless of who executes the measurement: someone must own the truth, and it cannot be the party selling, or even the one buying, the ads.

A better path forward

This industry doesn’t lack intelligence or ambition. It lacks a measurement culture grounded in independence and evidence. Marketers deserve clarity about what’s truly driving growth. Vendors that can prove genuine incrementality should welcome that scrutiny; everyone else will raise their game or fade away.

If marketers spent half as much energy insisting on credible causal measurement as they do chasing vanity metrics, the entire ecosystem would benefit. Media sellers would compete on actual performance, not on weaponized opacity. Agencies would be valued for insight, not self-preservation. CFOs would trust marketing again.

The principle that scales

Independence isn’t optional. It’s the first condition of truth. Many disciplines that measure cause and effect learned this long ago. Advertising is simply overdue to catch up.

If you’re still taking the media company’s ROI slide deck at face value, well, I do live in Brooklyn. Maybe you'd be interested a nice shiny bridge?

The Compounding Power of Long-Term Advertising: A Review of the Evidence

A question came up on the Research Wonks list about the impact of advertising short-term vs. long-term. (If you don't know the Wonks, sign up at ResearchWonks.com: forum of ~1500 media researchers.)

I googled then AI-ed. Below are some influential works on the subject. ChatGPT summarizes the consensus thusly:

Long-term impact is typically 2–5× the short-term effect. This ratio appears consistently across academic (Hanssens, Mela), industry (Sequent Partners, Gain Theory), and practitioner (Binet & Field) research.

Short-term metrics underestimate ROI. Campaigns optimized for near-term sales often misallocate budgets away from high-ROI brand building.

Different mechanisms drive each timescale: short-term activation (rational persuasion, promotions) vs. long-term brand effects (emotional memory, reduced price sensitivity, loyalty).

Sustained investment compounds results. Continuing advertising reinforces brand memory and repeat purchasing; stopping spend causes rapid decay.

Media and creativity matter. Broad-reach, emotional campaigns (especially on TV and high-quality digital) generate stronger long-term multipliers.

Best practice: balance roughly 60% brand / 40% activation spending and evaluate outcomes over multi-year horizons to capture the full economic impact.

Evaluating Long-Term Effects of Advertising, Sequent Partners, 2014

Short- and Long-term Effects of Online Advertising: Differences between New and Existing Customers, Breuer et al., 2012

What Is Known About the Long-Term Impact of Advertising, Hanssens, 2011

The Long-Term Impact of Promotion and Advertising on Consumer Brand Choice, Mela et al., 1997

The Long and the Short of It, Binet et al.,

Focusing on the Long-term: It’s Good for Users and Business, Hohnhold, 2015

Five key results from our long-term impact of media investment study, Chappell, Gain Theory

Giving Marketing the Credit it Deserves, Rubinson, TransUnion, MMA

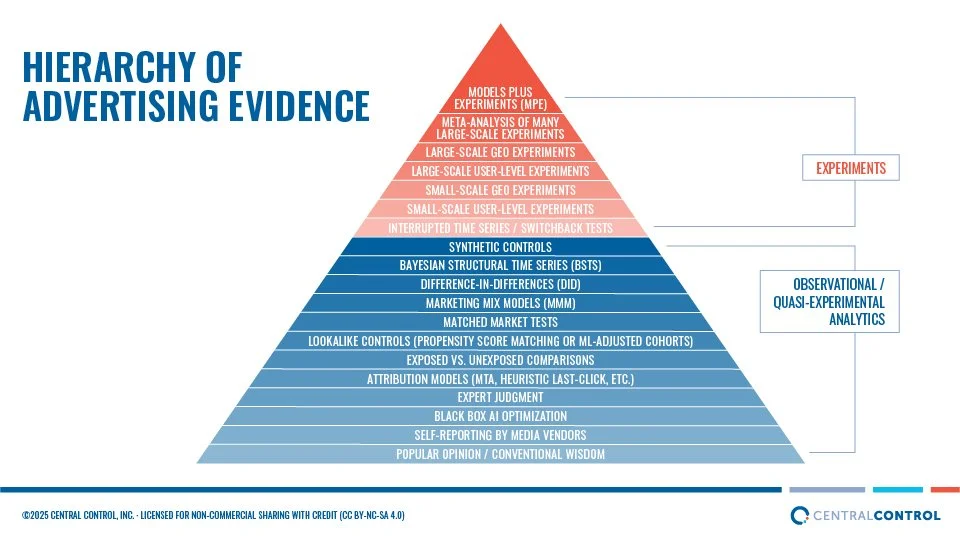

The Hierarchy of Advertising Evidence

In medicine and other sciences, the “Hierarchy of Evidence” ranks research methods by the strength of their causal claims, with meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials at the top and anecdotal opinion at the bottom. Advertising faces the same challenge: separating true incrementality from correlation. This hierarchy adapts that framework to advertising, showing how experimental methods — ideally randomized controlled trials (RCTs) — provide the most credible evidence of causal impact. Quasi-experimental and observational approaches, such as marketing mix models, synthetic controls, or attribution, remain widely practiced and valuable, especially when experiments are impractical (e.g., in small national markets or for channels like in-store promotions). Still, because these approaches lack randomization, they depend on modeling choices and statistical assumptions that are harder to verify, and thus they are subject to bias, overfitting and provide less certain evidence of causal impact than experiments.

Experiments

Models Plus Experiments (MPE) – Most rigorous framework: routinely validating MMM (or other models) with RCTs; combines scale of models with causal credibility of experiments.

Meta-Analysis of Many Large-Scale Experiments – Aggregating results across multiple RCTs; strongest external validity.

Large-Scale Geo Experiments (Cluster RCTs) – Random assignment of all geo regions within a country (e.g., DMAs); a consistent, robust, and scalable framework applicable across virtually all media channels.

Large-Scale User-Level Experiments – Randomizing millions of IDs; high internal validity but limited by cross-device fragmentation and low match rates, noisy for measuring small ad lifts.

Small-Scale Geo Experiments – Still randomized but less power, higher risk of idiosyncratic bias from a few markets.

Small-Scale User-Level Experiments – Feasible but often underpowered; generalizability limited.

Interrupted Time Series / Switchback Tests – Turning campaigns on/off repeatedly; can work if treatment effect is immediate and reversible, but vulnerable to temporal confounds.

Observational / Quasi-Experimental Analytics

Synthetic Controls – Weighted combination of control units to construct a “synthetic twin”; can provide credible counterfactuals but sensitive to donor pool and overfitting. (E.g., Meta's GeoLift R package.)

Bayesian Structural Time Series (BSTS) – Flexible probabilistic framework for counterfactual forecasting with covariates, trend, and seasonality; powerful but dependent on priors and specification choices. (E.g., Google's CausalImpact R package.)

Difference-in-Differences (DiD) – Compares changes in treated vs. untreated groups over time; intuitive and widely used but hinges on the parallel trends assumption.

Marketing Mix Models (MMM) – Longstanding regression framework using aggregate longitudinal data to estimate channel contributions; offers a holistic view of the mix but causal claims depend on assumptions unless validated by experiments.

Matched Market Tests – Selects untreated markets that resemble treated ones; easy to explain but prone to hidden bias.

Lookalike Controls (Propensity Score Matching or Machine Learning–adjusted cohorts) – Construct control groups matched on demographics, purchase history, or other observables; widely used in research panel-based lift tests but subject to hidden bias from unmeasured factors.

Exposed vs. Unexposed Comparisons – Naïve lift tests comparing those who saw ads to those who didn’t; easy to run but confounded by targeting bias.

Attribution Models (MTA, heuristic last-click, etc.) – Useful for exploring customer journeys, but correlation-based and not causal evidence.

Expert Judgment – Can inform hypotheses or priors, but not empirical evidence.

Black Box AI Optimization – Proprietary “incrementality” claims without transparency; credibility requires experimental validation.

Self-Reporting by Media Vendors – Metrics reported by the seller; rife with bias and not reliable for causal claims.

Popular Opinion / Conventional Wisdom – Lowest rung; anecdotal, not evidence.

How to interpret results from a randomized controlled experiment correctly

Screenshot of reporting from Central Control’s platform Experiment Designer

In the Research Wonks forum (recommended for all marketing analysts: visit researchwonks.com for details), I was asked my opinion on a thread titled "Does stat testing encourage the wrong decisions?" The heart of the question was how to interpret tests that aren't deemed quite "statistically significant," yet the profit value of the product is very high and purchase rates are very low (e.g., boats, solar panels, home owner's insurance).

Here is a modified version of my response, which is really a bit of an explainer on experimentation statistics themselves. As I noted in an earlier post in the forum, all of this pertains to well-constructed randomized controlled trials (RCT). If your definition of a test is relying on synthetic controls, matched markets or other quasi experimental methods, I'm much more skeptical of the results overall. More on that below.

Marketers often fixate on the 95% confidence level as the determinant of whether a test was “valuable” or not, when that's only one component of what makes an experiment result meaningful. It’s also often misunderstood.

Confidence level (CL) measures the likelihood that a result is a false positive — a Type I error. It’s not really saying “there was almost certainly a positive lift.” It’s saying that if you ran the test under the same conditions an infinite number of times, about 5% of the time you’d see a lift when in fact there wasn’t one. In other words, a false positive (Type I error).

The p-value of the test has an inverse relationship to the CL: a p-value under 0.05 indicates significance at the 95% CL.

It goes without saying that this foundation of statistics clearly describes an impossibility: the threshold of infinity notwithstanding, in advertising, test conditions are always unique, where each is a one-time snapshot of a combination of the creative, offer, audience, media, point in time, etc. But statistics is theoretical stuff. In a class on regression I once took, the professor described the concept of a “parent population,” being the theoretical infinite number of samples you could draw under the model, and the “daughter population,” which is the single sample you actually observed. The p-value, and most other statistical metrics, refer back to the likelihood that your daughter population correctly represents the “true” (theoretical) population.

Power describes the likelihood that your test will detect a positive result if one really exists. The common convention in experiment design is 80% power, which can feel low, since it’s answering the critical question: “Will I actually detect a lift if it’s there?” For experiments supporting high-stakes decisions, you might power for 90%. Unfortunately, power isn’t something you get as a marker in the results (like the p-value); it’s a design property, determined up front by inputs including sample size and the effect size you care about.

The maddening part is: with 80% power, if you fail to reject the null (i.e., no significant lift detected), there’s still a 1 in 5 chance that a true lift of the size you powered for was actually present, but your test missed it due to random chance, such as an unlucky draw of randomly assigned experiment units, ill-winds blowing from the south, etc. This is a Type II error, a false negative.

Which leads to three other important topics: confidence intervals, Bayesian thinking, and the value of an accumulated body of evidence.

Confidence intervals (CIs) are often neglected in superficial reporting of test results, but they’re crucial for interpretation. A CI shows the plausible range of effect sizes given your data, which bears on the original question in the Wonks forum: how to interpret significance in the case of high-value, low incidence transactions.

Ideally, results should look like: “Estimated lift = 5%, p = 0.04, 95% CI = +0.2% to +9.8%.” The p-value tells us the result just clears the 95% confidence level (so the false-positive risk is controlled at 5%). The CI tells us the range is fairly wide: the true lift could be as small as +0.2% or as large as +9.8%. So, even with a test that is "significant" at a 95% CL, the actual sales impact could vary widely, which is key for ROI. The measured effect size is really just a point estimate.

The formula is: CI = Estimate ± (Zα/2 × SE)

If you're using a 90% (or 80%) confidence level, and the lift is deemed positive but the p-value is > 0.05, then the 95% CI will straddle zero — meaning the data are consistent with no effect, a small positive effect, or even a negative effect. That’s why 95% CL is a useful rule of thumb, as a p-value of less than 0.05 assures the whole range of the CI will be greater than zero.

Beware the temptation to run one-tailed tests in ad experiments, where the presumption is the effect could only be positive. Ads can backfire. Think of the X10 camera from years ago — pioneer of the notorious pop-under ad format — that so annoyed people it arguably created negative lift. That logic also shows up in uplift modeling, where one audience segment is “sleeping dogs,” whose purchase likelihood can be harmed by advertising.

Bayesian analysis offers a more flexible interpretation than the rigid frequentist thresholds. Most MMM models today are Bayesian. In that mindset, even a p-value of 0.15 can be treated as evidence pointing toward a positive lift — not definitive, but suggestive, and potentially worth acting on depending on priors and expected ROI.

Finally, I always stress that the greatest confidence comes not from any one test but from a body of evidence built through repeated RCTs. In the hierarchy of evidence, the only thing stronger than a single well-run RCT is a meta-analysis of many of them. The closer you get to that “infinity of tests,” the more solid your knowledge becomes. Big advertisers, agencies, MMM shops, and publishers who accumulate 10s, then 100s, then 1000s of RCTs build a serious moat in their understanding of what really works across ad formats, CTAs, publishers, channels, product categories, and so on.

Of course, as I said at the top of this essay, all of these statistics are on shaky ground if your “testing” relies on synthetic controls, matched markets, propensity scores, machine learning, or other forms of quasi-experiments. Quasi-experiments can be useful if true RCTs are infeasible (rare in advertising) and/or if the expected effect size is very large. But if you’re chasing a 1-10% effect with a quasi-experiment, I wouldn’t bet the farm.

I wrote recently on LinkedIn that with enterprise AI systems poised to take over media planning, there’s a real danger those systems will train on quasi-experimental results — which pervade ROI measurement in advertising — and institutionalize bad learnings, creating a huge “knowledge debt” that will take years to unwind. Garbage in, garbage out.

Recommended further reading on the subject:

Close Enough? A Large-Scale Exploration of Non-Experimental Approaches to Advertising Measurement (Gordon et al., 2022)

Predictive Incrementality by Experimentation (PIE) for Ad Measurement (Gordon et al., 2023)

Enterprise AI is coming, and it's about to learn all the wrong lessons about marketing effectiveness (my essay)

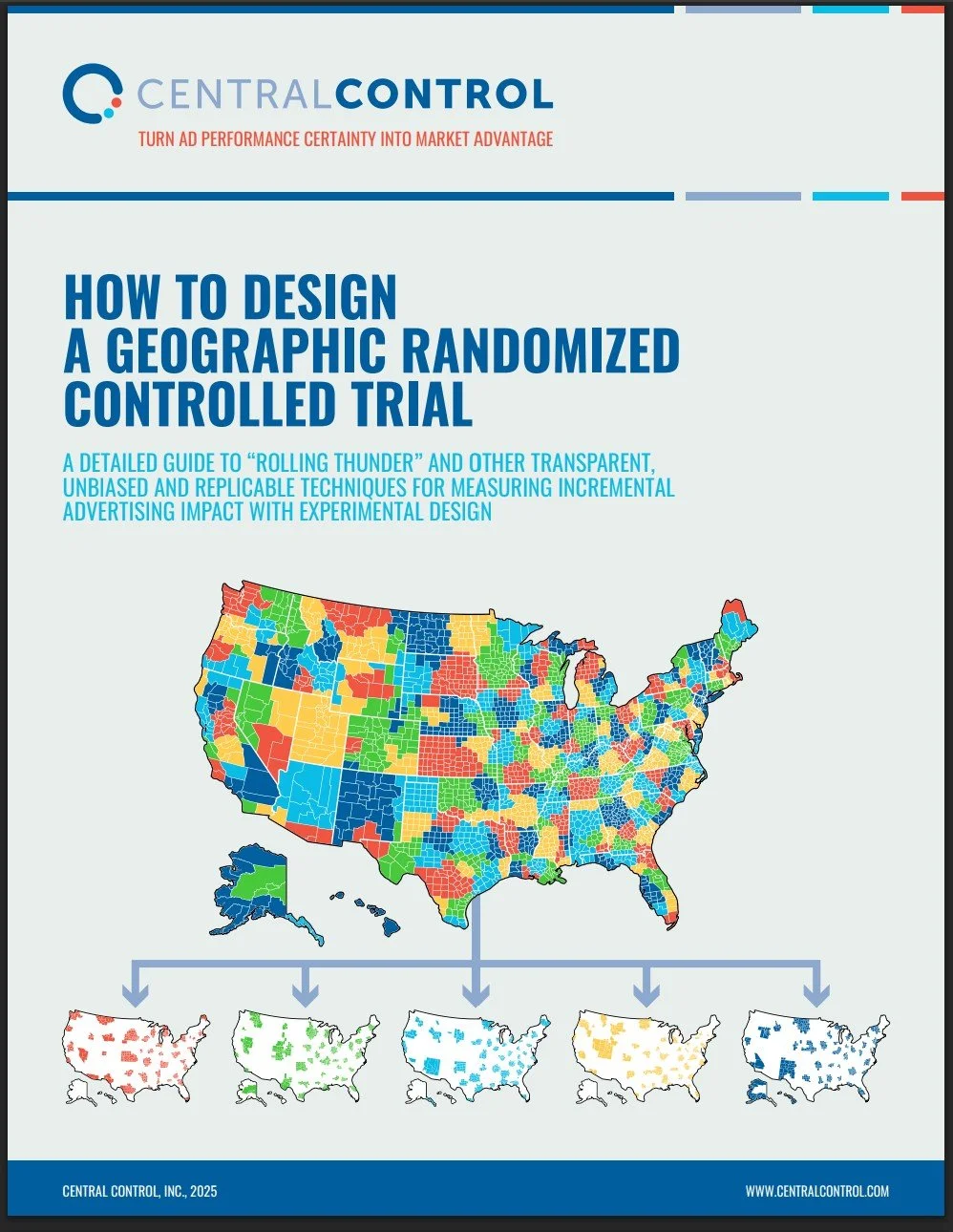

How to Design a Geographic Randomized Controlled Trial (a detailed, 50+ page whitepaper by Central Control, a big hit with experimentation experts)

NEW WHITEPAPER: How to Design a Geographic Randomized Controlled Trial

Download the whitepaper here (no registration required).

After years of advocating for better advertising measurement, I'm excited to share a comprehensive guide that doesn't just explain WHY geographic RCTs are superior for measuring true incremental ROI, it shows exactly HOW to implement them.

This 50+ page whitepaper includes:Step-by-step design frameworks for "Rolling Thunder" and other experiment designs

Detailed Python code examples for randomization, analysis, and power calculations

Statistical methodologies that deliver unbiased, transparent, replicable results

Implementation checklists to ensure experimental integrity

Real-world case studies demonstrating the approach in action

For too long, marketers have relied on observational and quasi-experimental methods like matched market tests, synthetic controls, and attribution models, which tend to systematically overstate performance. As I've written previously, these approaches might be "customer pleasing," but they're leading to billions in misallocated ad spend.

The truth is that geographic RCTs aren't comparatively difficult or expensive to implement, they're just unfamiliar to many practitioners. This guide demystifies the process and provides everything you need to start measuring true incremental impact.

Download the whitepaper here (no registration required).

If you're responsible for major advertising investments and want to know what's really working, this is your roadmap to better measurement and better results. For questions, training or support implementing these techniques, please reach out. I'm always happy to discuss how this methodology can transform your measurement approach and marketing effectiveness.

#MarketingMeasurement #Incrementality #ExperimentalDesign #AdvertisingEffectiveness #DataScience #iROAS

Enterprise AI is coming, and it's about to learn all the wrong lessons about marketing effectiveness

🚨 TL;DR: Most advertisers will train AI systems on flawed campaign measurement data, risking a generation of misinformed media planning.

By Rick Bruner, CEO, Central Control

Last week's I-COM Global summit was, once again, a highlight of the year for me. While its setting is always spectacular (Menorca was no exception) and the fine food and wine certainly helped, what truly distinguishes I-COM is the quality of the discussions, thanks to the seniority and expertise of attendees from across the ad ecosystem.

The dominant theme this year: large organizations preparing for enterprise-scale AI. We heard from brands including ASR Nederland, AXA, Bolt, BRF, Coca-Cola, Diageo, Dun & Bradstreet, Haleon, IKEA, Jaguar, Mars, Matalan, Nestlé, Reckitt, Red Bull Racing, Sonae, Unilever, and Volkswagen about using AI to optimize virtually every facet of marketing: user attention, content creation, creative assets, CRM, customer engagement, customer insights, customer journey, data governance, personalization, product catalogs, sales leads, social media optimization, and more.

Two standout keynotes, by Nestlé's Head of Data and Marketing Analytics, Isabelle Lacarce-Paumier, and Mastercard's Fellow of Data & AI, JoAnn Stonier, focused on a critical point: AI’s success hinges on the quality of its training data. Every analyst knows that 90% of insights work is cleaning and preparing the data.

The situation couldn’t be more urgent. My longtime friend Andy Fisher, one of the few industry experts with more experience running randomized controlled experiments than I, pointed out that most companies still don't use high-quality tests to measure advertising ROI. As a result, they’re about to embed flawed campaign conclusions into AI-driven planning tools, creating a knowledge debt that could take decades to rectify.

As I’ve written here recently, most advertisers still rely on quasi-experiments at best, or decade-old attribution models at worst. Even today’s favored quasi-methods — synthetic controls, debiased ML, stratified propensity scores — offer only the illusion of experimental rigor, often delivering systematically biased results.

By contrast, randomized controlled trials, especially large-scale geo tests, remain the most reliable evidence for determining media effectiveness. Yet they’re underused and underappreciated.

Why? Because quasi-experiments are “customer pleasing,” as an MMM expert recently put it. They skew positive, so much so that Meta now mandates synthetic control methods (via its GeoTest R package) for official experimentation partners, one told me the other day, because the results are reliably favorable to Meta's media.

That might be fine if those tests stayed in the drawer as one-off vanity metrics. But with enterprise AI, they won’t. They’ll be unearthed and fed, by the dozens or hundreds, into new automated planning systems, training the next generation of tools on false signals and leading to years of misallocated media spend.

The principle is simple: garbage in, garbage out.

Saying goodbye to the Mediterranean for another year, all the Manchego and saffron bulging in my suitcase couldn't soothe my unease about the future of marketing performance. It’s time to standardize on real evidence. Randomized experiments should be the norm, not the exception, for ROAS testing. The future of AI-assisted media planning depends on it.

Gain Market Share by Disrupting Bad Ad Measurement

"It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it."

- Upton Sinclair

Do you ever get the feeling that your advertising performance metrics are mostly baloney? If so, this article is for you.

The advertising industry desperately needs brave, skeptical individuals willing to demand better evidence of what actually works—from media partners, agencies, measurement firms, and industry bodies.

But does anyone really care? Currently, over 90% of media practitioners either don't grasp the shortcomings of their current practices, have conflicting incentives, or are content with CYA reporting theater, leading to poor investment decisions.

Can you trust big tech companies like Google and Meta to tell you what's effective? After all, they've got those smarty-pants kids from MIT and Stanford, right? Surely you jest. Do you really expect them — who already receive most of your budget — to suggest you spend more on Radio, Outdoor, or Snap? Read the receipts.

What about your ad agency — isn't that their job? Actually, no. Agencies get paid based on a percentage of ad spend, so why would they ever suggest spending less? And if they're compensated on a variable rate, e.g., 15% of programmatic spend vs. 5% of linear, it's no surprise they're steering budgets toward easier and higher-margin channels.

How about your in-house analytics experts? Well, first they'd need to imply they've been measuring iROAS poorly for years. Awkward. The head of search marketing, whose budget might shrink if real measurement proved poor performance? Unlikely. The CMO? Only if she's new and ready to shake things up—your best hope for disruption.

As Upton Sinclair aptly wrote, "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it."

We're calling on:

Private equity firms seeking hockey-stick growth

CFOs skeptical of ad metrics, viewing marketing as a cost center

Media sellers, large and small, being strangled by Google and Meta’s duopoly

Mid-tier DTC brands not yet hypnotized by synthetic control methods or captive to big tech

Today's "performance" measurement is largely flawed, built on bad signals, lazy modeling, and vanity metrics. The consequences are poor decisions, wasted budgets, and lost market share.

Avoid these unreliable measurement approaches:

Matched market testing

Synthetic control methods

Attribution models

Quasi-experiments

Black-box "optimization" solutions like PMax and Advantage+

None of these offer solid evidence. Some might be "better than nothing," but that's hardly the standard you want for multimillion-dollar decisions. At worst, they're self-serving illusions from platforms guarding their own margins, not advertiser interests.

Our profession embraces these weaker standards when better measurement is easily attainable. Marketing scientists have never met a quasi-experimental method they don't like — dense statistics are so much fun! But randomized controlled trials (RCTs) — deemed the best evidence of causality by science, with straightforward math — are falsely labeled as "too hard."

RCTs remain the only reliable method to isolate causal impact and identify true sales lift. Claims about their complexity or expense are myths perpetuated by those benefiting from the status quo.

Today's trendiest method, Synthetic Control Method (SCM), is essentially matched market testing (DMA tests familiar since the 1950s) boosted by statistical steroids. You pick DMAs to represent a test group (the first mistake) and construct a Frankenstein control from a weighted mashup of donor DMAs.

SCM excels when an RCT truly isn't possible — like assessing minimum wage impacts, gun laws, or historical political policies such as German reunification. These scenarios can't ethically or practically be randomized. But advertising? Advertising is perhaps the easiest, most benign environment for RCTs. Countless campaigns run daily, media is easily manipulated, outcomes (sales) are straightforward, quick to measure, and economically significant. There are few valid reasons not to conduct RCTs in advertising.

The first rule of holes is "Stop digging." The first rule of quasi-experiments is "Use them when RCTs are unethical or infeasible." That's almost never true for ad campaigns.

Synthetic Control Method is problematic because it:

Offers weaker causal evidence than RCTs

Is underpowered for ad measurement: the academic literature on SCM cite social policies resulting in effect sizes >10%, much greater than large marketers can expect from advertising

Lacks transparency (requires advanced statistical knowledge)

Is not easily explainable to non-statisticians

Lacks replicability (each instance is a unique snowflake dependent on many choices)

Lacks generalizability (blending 15 DMAs to mirror Pittsburgh still doesn't reflect national performance)

I've yet to hear a compelling reason for choosing SCM over RCT for ad measurement that wasn't self-interested rationalization. For more on the how, why and when to use geo RCTs, see my previous essay in this series.

As a global economic downturn looms, many advertisers will unwisely slash budgets without knowing what's genuinely effective. Don't make mistakes that could threaten your company's future. Measure properly — cluster randomized trials are your best path to true advertising ROI.

Advertisers seeking accurate ROAS should use large-scale, randomized geo tests

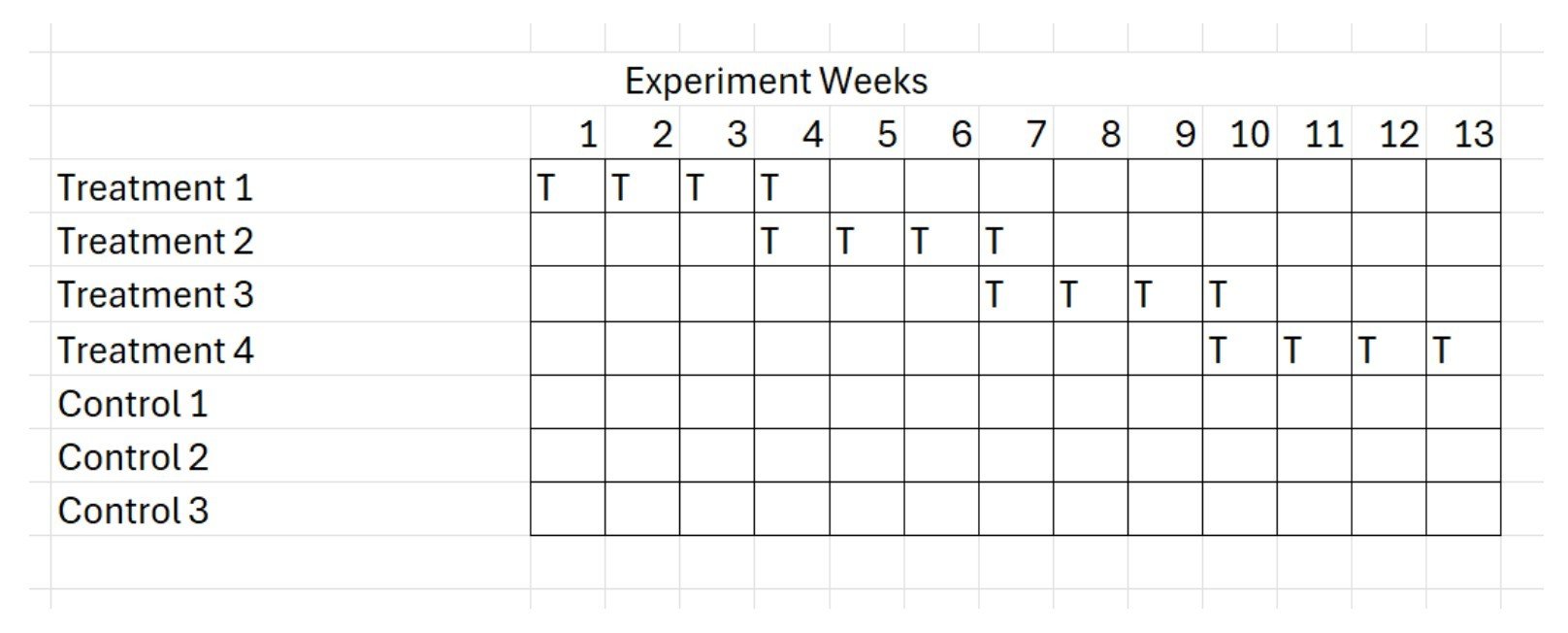

Multi-armed Cluster Randomized Trial design using DMAs for national ad campaign

The smallest Fortune 500 companies have revenue on the order of $10 billion, meaning they are likely spending at least $1 billion on paid advertising. If your company is spending hundreds of millions on advertising, there is no excuse for optimizing ROI with half measures. Yet that is exactly what most companies do, relying on subpar techniques such as attribution modeling, matched market tests, synthetic control methods and other quasi-experimental approaches.

Quasi-experiments, by definition, lack random assignment to treatment or control conditions. The first rule of quasi-experiments, as the methodological literature consistently makes clear, is that they should be used when randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are "infeasible or unethical."

As Athey and Imbens (2017) state: "The gold standard for drawing inferences about the effect of a policy is a randomized controlled experiment. However, in many cases, experiments remain difficult or impossible to implement, for financial, political, or ethical reasons, or because the population of interest is too small."

For advertising measurement, it's rarely unethical to run an RCT, and it's almost always feasible. Decisions to opt for lesser standards, say the bronze or tin of quasi-experiments or attribution, usually stem from a lack of understanding of how significantly inferior those methods are for causal inference compared to RCTs, or misplaced priorities about the perceived cost of high-quality experiments.

As for the general accuracy of quasi-experimental methods, many practitioners assume they provide at least "directionally" correct results, but in reality such results can often be misleading or inaccurate to a degree that's difficult to quantify without benchmark randomized trials.

The seminal paper "Close Enough? A Large-Scale Exploration of Non-Experimental Approaches to Advertising Measurement" (Gordon et al., 2022) demonstrated this. It took some 600 Facebook RCT studies and reanalyzed their results using double/debiased machine learning (DML) and stratified propensity score matching (SPSM), among the most popular forms of quasi-experiments, the types used by many panel-based ad measurement companies. In keeping with the journalistic adage that the answer to any headline posed as a question is “no,” the researchers found the quasi-experimental approaches were "unable to reliably estimate an ad campaign's causal effect."

Regarding the perceived cost of large-scale experiments: The primary cost to advertisers isn't in conducting rigorous RCTs, but rather in the ongoing inefficiency of misallocated media spend. For companies investing hundreds of millions annually in advertising, the opportunity cost of suboptimal allocation—both in wasted dollars and unrealized sales potential—can substantially outweigh the investment required for proper experimental design.

Witness Netflix, which, almost 10 years ago, assembled a Manhattan Project of foremost experts in incrementality experimentation. Their cumulative RCT findings led them to eliminate all paid search advertising. This counterintuitive but data-driven decision would likely never emerge from attribution modeling or quasi-experimental methods alone, highlighting the unique value proposition of rigorous experimental practice.

In terms of the best type of experiments for advertising effect, there has been a growing consensus among practitioners that geographic units are more reliable today than user, device or household units. For years, the myth of the internet's one-to-one targeting abilities gave rise to the belief that granular precision was synonymous with accuracy. While this was never really true, the rise of privacy concerns and the deterioration of granular units of addressability now mean that user-level experiments are less accurate than tests based on geographic units such as designated market areas (DMAs). The irony is that identity is not necessary for deterministic measurement.

Beyond privacy problems and the need for costly technology and intermediaries in the form of device graph vendors and clean rooms, the match rates of user-level units between the media where they run and the outcome data, e.g., sales, of the dependent variable are usually too weak for experimentation, e.g., below 80%. Even at higher match rates, measuring accurately for typical ad sales effects of around 5% or less is unachievable due to spillover, contamination and statistical power considerations.

Postal codes would be an ideal experiment unit, given that they number in the thousands in most countries, a level of granularity that fortifies the distribution of unobserved confounding variables and is a large enough base of units to measure small effect sizes. But, as I argued in an AdExchanger article a few months ago, publishers seem unwilling to make the necessary targeting reforms to make them a viable experimental unit to fix the morass of digital advertising measurement.

That leaves DMAs, which thankfully work well in the large US market as an experiment unit for national advertisers willing to run large-scale tests with them. Geographic experiments broadly fall into a class of RCT known as cluster randomized trials (CRT), where the human subjects of the ad campaigns are clustered by regions. A key benefit of geo experiments is that they correspond to ZIP codes already in the transactional data in many advertisers' first-party CRM databases and third-party panels, enabling researchers to read the lift effect without any data transfer, device graphs, clean rooms or privacy implications. And, importantly, no modeling required.

Although there are only 210 DMAs in the US, and they vary widely by population size and other factors, collectively they represent a population of roughly 350 million people. Randomization is the most effective way to control for biases and unknown confounders among those varying factors and deliver internal validity to test and control group assignments.

A parallel CRT, with one test and one equal sized control group based on all 210 DMAs, is the most statistically powerful kind of design, especially appropriate for testing a medium not currently or regularly in an advertiser's portfolio.

For a suppression test, where the marketer seeks to validate or calibrate the effect size of a medium where its default status is always-on advertising in a given channel, such as television or search, a stepped CRT design, where ads are turned off sequentially across a multi-armed experiment, is a good option. The stepped approach allows the advertiser to ease into a turn-off test and monitor sales, such that the test can be halted if the impact is severe. They also require less than 50% of media weight to be treated, albeit at the sacrifice of statistical power: the illustration here shows a design using multiple test and control arms that put only 18% of the total media weight into cessation treatment.

Multi-armed Rolling Stepped Cluster Randomized Trial design, withholding only 18% of media weight

Stratified randomization, statistical normalization of DMA sales rates, and validation of the randomization on covariates such as market share and key demographic variables can be incorporated into the design to strengthen confidence in the results. Ultimately, the best evidence of true sales impact is not a single test but a regular practice of RCTs, in complement with other inference techniques, such as market mix modeling and attribution modeling, so-called unified media measurement, or what we call MPE: models plus experiments.

This kind of geographic experimentation should not be confused with matched market tests (MMT) or its modern counterpart synthetic control methods (SCM). Matched market testing has been used for decades by marketers, and its shortcomings are well understood in the inability for one or a few DMAs in control to replicate the myriad exogenous conditions in the test that could otherwise explain sales differences between markets, such as differing weather conditions, supply chains and competitive mixes, to name a few.

SCM has gained a loyal following in recent years as a newer approach to the same end, using sophisticated statistical methods to improve the comparison of a few test and control geographies. The approach, however, is still fundamentally a quasi-experiment, subject to the inherent limitations of that class of causal inference, namely its reduced ability to control for unobserved confounds, limited generalizability to a national audience and comparatively weaker statistical power, based on a few DMAs compared to all DMAs in the case of large-scale randomized CRTs. While there's ongoing work to improve SCM, I haven't seen any methodological papers claiming SCM to be more reliable than RCT, despite claims to that effect from some advertising measurement practitioners.

As Bouttell et al. (2017) state, "SCM is a valuable addition to the range of approaches for improving causal inference in the evaluation of population level health interventions when a randomized trial is impractical."

Running tests with small, quasi-experimental controls is a choice, not a necessity for most advertising use cases. True, no one dies if an advertiser misallocates budget, as can be the case with health outcomes, where clinical trials (aka RCT) are often mandated for claims of causal effect. But companies lose market share, and marketers lose their jobs, particularly CMOs. When millions or billions in sales are at stake, cutting corners in the pursuit of knowing what works can be ruinous to a brand's performance in a market where outcomes are measurable and competition is zero sum.

Recession-Proofing Your Ad Mix: Measure Twice, Cut Once

The hedge fund guru Warren Buffett, speaking of naïve investment strategies, famously said, “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who's been swimming naked.”

The same could be said for marketers whose paid media investments rely on simplistic ROAS measurement.

Is a recession coming? No one can say for sure. A couple of years ago, most economic pundits thought so. Historically, recessions occur every 6–10 years, and it’s been 16 years since the last real one. The new administration’s shock-and-awe economic policies have people wondering again.

Would your organization be ready? When corporations shift into austerity mode, research departments are the first to go, followed by deep marketing budget cuts. But what would you cut?

Many marketers worry about "waste" in ad spending. Our work with clients suggests a far greater risk: cutting the wrong things—the investments actually driving the highest sales ROI. Faulty measurement often blinds leadership to what truly works.

Consider one case study: We worked with a Fortune 100 brand to measure the effectiveness of one of their biggest digital media channels. The long-time CMO had lost faith in their attribution analytics—and rightly so. He believed they were overpaying and wanted to slash the channel’s $100 million annual budget in half. But, wisely questioning his assumption, he brought us in.

Long story short, we found that the channel drove 3% of all new client acquisitions—but not where they expected. The impact was entirely through their offline sales channels, which accounted for the majority of their business. Yet all their attribution tracking was focused on online conversions.

Had they cut that $50 million in ad spend, they would have jeopardized $1.5 billion in sales. Only our rigorous, randomized experiment-based testing—leveraging anonymized first-party CRM sales data—revealed the truth. The digital media giants they were paying simply had no visibility into this.

Attribution models, clicks, propensity scores, quasi-experiments, synthetic controls, lab tests—I wouldn’t bet the farm on any of them.

Sometimes, the best wisdom comes from time-tested axioms, like the one passed down by carpenters and tailors: “Measure twice. Cut once.”

Don’t short-change your measurement. Jobs—yours included—and even your company’s survival are the stakes.

Media Companies’ Survival Depends on More Accurate ROAS Measurement

Guideline Spend is a census of all media dollars transacted through the biggest 12 agencies in the US market.

Do you hear that giant sucking sound? That’s the advertising economy draining billions into the bank accounts of Google, Meta, and Amazon

Why do advertisers keep shifting more and more of their budgets to these digital giants, year after year, at the expense of other media companies? Sure, they have eyeballs and engagement, but that’s only part of the story.

If this were a (very lousy) game show—Advertising Family Feud—the top answer would be obvious: “Measurability!” Ding, ding, ding!

For most media companies outside the Big Three, proving their ROI has been historically undervalued due to flawed ad performance measurement is now an existential priority. Engagement metrics, attention scores, brand impact studies, attribution models, and quasi-experimental lift reports won’t cut it. Neither will claims about “quality audiences” or other vague promises.

Even mediocre marketers are skeptical of these metrics. The smartest ones outright dismiss them as irrelevant to what matters most: incremental sales impact.

So, how can media companies bridge the gap and prove their value?

The Case for Geographic Experimentation

The easiest and most effective way to deliver what advertisers need—transparent and credible proof of ROI—is by implementing sound geographic experimentation. Better yet, develop an in-house center of excellence around this approach.

Big Digital has spent years perfecting its tools for “proving” (and often feigning) ad performance. These include:

Marketing Mix Modeling (MMM) tools like Google’s Meridian and Meta’s Robyn.

Auction-based randomized experiments, also known as “ghost ads,” which Apple’s privacy measures have impaired in recent years.

Black-box AI optimization engines like Google’s Performance Max and Meta’s Advantage+, which are difficult to validate independently.

These tools make it easy for advertisers to spend more, while other media companies struggle to offer competitive proof of performance. Resistance to Big Digital often feels futile—but it doesn’t have to be.

TV, Radio, and Outdoor: Still Undervalued

It’s likely that TV ROI is undervalued. The same goes for traditional channels like radio and outdoor, which still capture attention just as effectively as ever. But without credible evidence of their true impact, they’ve largely fallen off the marketing mix radar.

And what about other digital properties? Are they outperforming Meta and Google? With today’s ROAS measurement practices, it’s anyone’s guess.

DMA Testing: A Path Forward

DMA-based experiments could be the best hope for media companies looking to prove their value. As discussed in my recent AdExchanger article, ZIP-code-based targeting could take things a step further, but it would require heavier lifting by media companies, and I’m not holding my breath.

Large-scale, randomized DMA experiments are emerging as a powerful, scalable method for ROAS measurement. By randomizing all 210 DMAs into test and control groups, advertisers can conduct transparent, replicable tests that provide irrefutable ROI evidence. Compared with user-level experiments, large-scale geographic experiments are far easier to implement, much less costly, and more accurate, due to noise and matching-biases in user-level frameworks.

This was a key topic in our recent webinar with MASS Analytics, an MMM specialist, describing how MPE (Models Plus Experiments) is a growing practice to calibrate the accuracy of mix models with regular ROAS experiments.

The Bottom Line

Media companies that adopt these rigorous testing methodologies, or even make them simple for advertisers to implement independently, have their best shot at countering claims of superior performance Google, Meta, and Amazon. If your channel truly adds value, transparent experiments will prove it—turning your “measurability gap” into a competitive advantage.

In a world dominated by Big Digital, investing in accurate ROAS measurement isn’t just a strategy—it’s a survival necessity.

Post Script

Thanks to Guideline for permission to share this data.

As Josh Chasin and Susan Hogan pointed out in the comments of this post on LinkedIn, that 29% share of spending shown in the chart is an even smaller share than the Big Three command of the total ad market, as Guideline's data includes only the spending of the largest ad agencies. Even more of the total goes to the biggest players thanks to the "long tail" of the market that does not go through the biggest agencies (i.e., through smaller agencies, large advertisers in-housing, and smaller advertisers buying direct).

Thankfully, large agencies still diversify their budget across more publishers compared to smaller advertisers, but even there the trend is not promising for the majority of media companies.

Calibrating Mix Models with Ad Experiments (Webinar Video)

Click here to view this webinar video

The next big wave in advertising ROI analytics is here! 🚀

After MMM and MTA comes MPE: Models Plus Experiments, a powerful approach that combines the strengths of modeling with the precision of experiments to supercharge your ROI insights.

View the video of our LinkedIn Live webinar, attended by 160 professionals as three renowned experts in the field delve into the details and best practices for leveraging MPE to drive smarter, more actionable marketing decisions:

🎓 Dr. Ramla Jarrar, President of MMM specialist MASS Analytics

🧮 Talgat Mussin, geographic experiment guru from Incrementality.net

📈 Rick Bruner, CEO of Central Control, Inc., expert on experiments for advertising impact

Five Forces That Could Further Roil the Ad Industry in 2025

I’ve always been a big booster of the ad industry—its role in funding free speech (i.e., media outlets) and its multiplier effect on GDP by driving sales. For decades, I’ve encouraged young people to pursue great careers in this field.

Lately, I’m not so sure. It would be nice to start the new year with an upbeat post, but this is what’s on my mind instead.

Last year saw Google and Meta, the two biggest media companies, shrink their ad-related workforces, while layoffs have become numbingly common among traditional media, agencies, and many digital platforms.

Some of this reflects over-hiring during the ad bubble of 2021, but there are macro trends—AI, programmatic buying, and higher interest rates pushing profitability—that aren’t going away anytime soon.

As we enter 2025, here are five events and trends that could spell continued challenges for professionals in the field.

1. Omnicom / IPG Merger

And then there were five. Of the biggest agency holding companies—Publicis, Dentsu, WPP, Havas, Omnicom, and IPG—only Publicis is thriving. When adjusted for inflation, the collective spending of these media-buying groups on advertising has shrunk since 2017, even as Fortune 1000 revenues have grown significantly relative to inflation.

Why the disconnect? Advertising is supposedly more efficient now, driving more sales for less money, but that seems an overly optimistic explanation. More likely, it’s due to brands in-housing budgets, shifting dollars to boutique agencies for niches like retail media and podcasting, and the downward pricing pressure of programmatic exchanges.

One thing you can count on from this kind of consolidation is job cuts.

2. TikTok’s Peril

President Trump has asked the Supreme Court to delay the January 19 deadline for banning TikTok, but his whimsies don’t inspire job security.

TikTok’s U.S. staff is surprisingly small—under 10,000—but highly efficient. If those employees hit the job market suddenly, it could flood an already competitive field with more A-listers on the heels of all those laid-off Google and Meta experts.

Beyond that, TikTok plays a unique role in the ad ecosystem, supporting hundreds of thousands of creators and millions of niche advertisers. Its closure would ripple across the economy.

3. TV Networks on the Chopping Block

Comcast and Warner Bros. Discovery are moving several networks into new business units to make their core companies more attractive to investors. Paramount is reportedly considering similar moves.

With Netflix, Amazon, and Apple spending heavily on hit shows, movies, and live sports, the pressure on traditional networks to maintain ad share is intense.

4. Pharmaceutical Advertising Under Threat

President Trump’s pick for health secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., wants to ban prescription drug ads on TV. Few other countries allow such ads. Legal challenges may prevent the ban. But anything seems possible these days. And, they did it to Big Tobacco, so there is a kind of precedent.

Pharma is one of the biggest ad categories after CPG, particularly for linear TV. Losing it would be a near-extinction event for some major media companies.

5. The Rise of AI-Driven ROI

To me, the most worrying trend is advertisers trusting platforms like Google’s Performance Max and Meta’s Advantage+ to spend ad dollars “efficiently” through black-box algorithms.

Say it out loud: “The biggest media companies will use secret formulas to spend my ad money most wisely.” That doesn’t sound fishy to you?

It’s like the sheep appointing the wolves their legal guardians.

The giveaway that this is a scam is they don’t even allow a backdoor for fair testing, such as an option to run geo experiments on top of the algos to independently confirm the so-called performance or advantage. No “trust, but verify”—only “trust us.”

Of course, it's no coincidence that the rise of this kind of auto-magic, self-reported ROI comes after years of agencies and smaller media companies cutting their own research departments to near zero.

But, aside from all that, Happy New Year! I’d love to hear comments about what I got wrong here and what silver linings I should be focusing on instead.

Meanwhile, if you want to figure out what’s really working in the mix, give us a call.

The only real ROAS is experiment-based, incremental ROAS

The only real return on ad spend (ROAS) is experiment-based, incremental ROAS.

Accept no quasi-experimental imitations.

ZIP Codes: The Simple Fix For Advertising ROI Measurement

(As published in AdExchanger.)

By Rick Bruner, CEO, Central Control

One of the hottest trends in advertising effectiveness measurement, especially with privacy concerns killing user-level online tracking, is geographic incrementality experiments. These experiments are cost-effective, straightforward and reliable, if done right.

Geo media experiments typically use large marketing areas, such as Nielsen’s Designated Market Areas (DMAs). Unlike traditional matched market testing, this modern approach involves randomizing DMAs, ideally all 210, into test and control groups. This way, advertisers with first-party data can measure true sales lift in house without external services. For those lacking in-house sales data, third-party panels, such as those from Circana and NielsenIQ, offer alternatives compatible with this kind of test design.

High-quality, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) – akin to clinical trials in medicine – are the best source of evidence of cause-and-effect relationships, including advertising’s impact on sales.

Statistical models, including synthetic users, artificial intelligence, machine learning, attribution, all manner of quasi-experiments and other observational methods are faster, more expensive and less transparent forms of correlation – not measurement of causation. They may be effective for audience targeting, but they are not for quantifying ROI.

Imagine, however, the potential for conducting geo experiments using ZIP codes instead of DMAs.

Targeting with ZIP codes

An advantage to DMAs is that they are universally compatible with all media types. ZIP codes, on the other hand, pose challenges to experiments in digital media. Targeting with ZIP codes online often relies on inference from IP addresses, which is unreliable and increasingly privacy-challenged. Geo-location signals from mobile devices also contribute ZIP codes to user profiles, which is bad for experiments, as a single device/account can be tagged with multiple ZIP codes based on where the user has recently visited.

A key to the reliability of this kind of geo experiment is ensuring that the ZIP codes used for randomized media exposures match the ZIP codes where audience members receive their bills, as recorded in company CRM databases. Each device and user should be targeted by only one ZIP code: their residential one.

To adopt this technique, media companies can take two transformative steps:

Use primary ZIP code targeting: Major players like Google and Meta already collect extensive user data, often appending multiple ZIP codes to a single device. For experiments, these companies should offer a “primary” zip code targeting option, based on the user’s profile or most frequently observed ZIP code for their devices.Implement anonymous registration with ZIP codes:

Publishers should require registration to access most free content, offering an “anonymous” account type that doesn’t require an email address. Users would provide a username, password and home ZIP code, enabling publishers to enhance audience profiles while maintaining user anonymity.

These strategies would significantly improve ROI measurement, offering a more powerful and simpler mechanism than cookies or other current alternatives. Unlike cookies, which were always unreliable for measuring ROI, these methods provide a privacy-centric, fraud-resistant solution that doesn’t require complex data exchanges, clean rooms, tracking pixels or user IDs.

Industry bodies like the IAB, IAB Tech Lab, MMA, ANA, MSI and CIMM should advocate for this approach, which would revolutionize advertising incrementality measurement.

With over 30,000 addressable ZIP codes compared to 210 DMAs, the potential for greater statistical power and more reliable ROI measurement is immense. As Randall Lewis, Senior Principal Economist at Amazon, told me, “the statistical power difference between user IDs and ZIP codes in intent-to-treat experiments can be small, with the right analysis methods.”

Adopting this approach would mark a significant leap forward, making high-quality experiments more accessible and reliable than ever before, ensuring a privacy-pure and fraud-proof approach to measuring advertising effectiveness.

The Future of Measuring Advertising ROI is "MPE": Models Plus Experiments

Marketing ROI measurement is going through a generational transformation right now. Following MMM (marketing/media mix models in the ‘90s), MTA (multi-touch attribution in the 2000s) now comes a new emerging best practice I call “MPE”: Models Plus Experiments.

MPE refers to a process of constant improvement to existing marketing ROI models, particularly MMM, by fine tuning model assumptions and coefficients with a practice of regular experiments for measuring incremental ROI.

The Gold Standard Is Not a Silver Bullet

Scientists consider the type of experiment known as a “randomized controlled trial” (RCT) to be the “gold standard” for measuring cause and effect, but the approach is not a silver bullet for advertisers.

Equivalent to “clinical trials” for proving efficacy in medicine – where outcomes of a test group are compared against those of a control group, where, critically, the test and control groups are assigned by a random process before the intervention of the experiment – RCT has a reputation among advertisers as being difficult to implement.